“Riveting and easily read in one sitting.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Clearly written and unusually lively.”

—Booklist

The decisive moments in a single life can change the world.

These books place you side by side with the subjects on the days that defined their lives and altered the course of history. Days of danger, days of fear, days of struggle, and days of triumph.

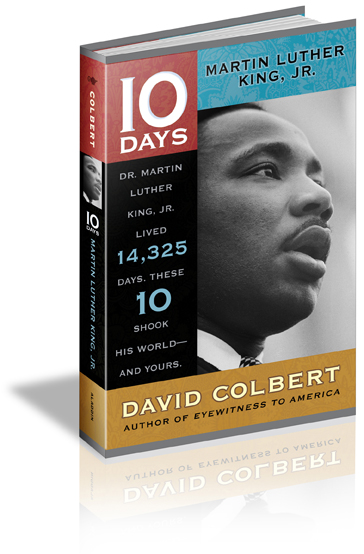

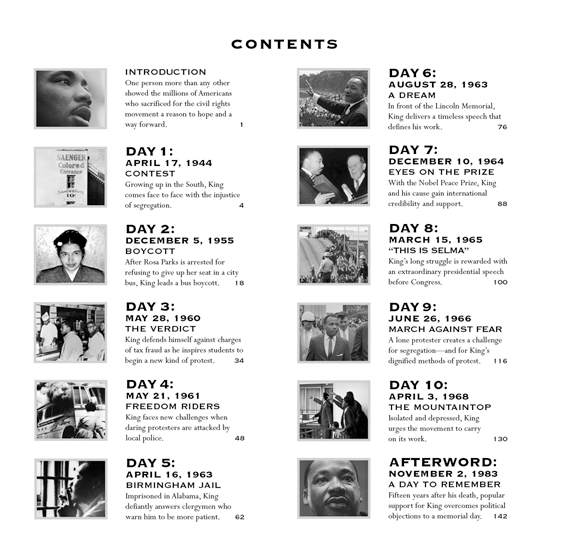

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lived 14,325 days. These 10 shook his world—and yours.

IntroductionThe civil rights movement succeeded because it had many brave organizers and supporters. Hundreds of men and women started local protests and initiatives that grew to national importance. Thousands—perhaps millions—risked their lives.

Yet there’s a lot of truth in the notion that Martin Luther King Jr. was special, a first among equals. He set an extraordinary challenge for himself and his movement: to achieve through peaceful victories what would have been difficult even for someone who used threats or violence. He was determined to change the minds of his opponents, not merely defeat them. King’s adherence to the ideal of non-violence was all the more admirable because he and his supporters faced so much violence themselves, often from the very law enforcement officers who should have been offering protection. It would have been easy to strike back. King refused to do that, and urged his colleagues to be equally as disciplined.

Despite being the focus of so much adoration, no one was more aware of the work done by others than King himself. One man who knew him said King “felt keenly that people who had done as much as he had or more got no such tribute. This troubled him deeply because there’s no way of sharing that kind of tribute with anyone else: You can’t give it away; you have to accept it. But when you don’t feel you’re worthy of it and you’re an honest, principled man, it tortures you. And it could be said that he was tortured by the great appreciation the public showed for him.”

King judged himself harshly and, despite his great achievements, was consumed by the work left to do. His murder, not long after his thirty-ninth birthday, left more work than he imagined. But the extraordinary changes in the United States that continue to take place since his death—the changes that he dreamed of—are proof of his lasting influence. In his relatively short life, just 14,325 days, these ten days changed his world and yours.

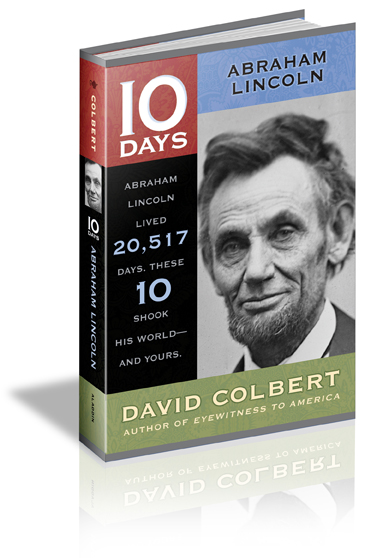

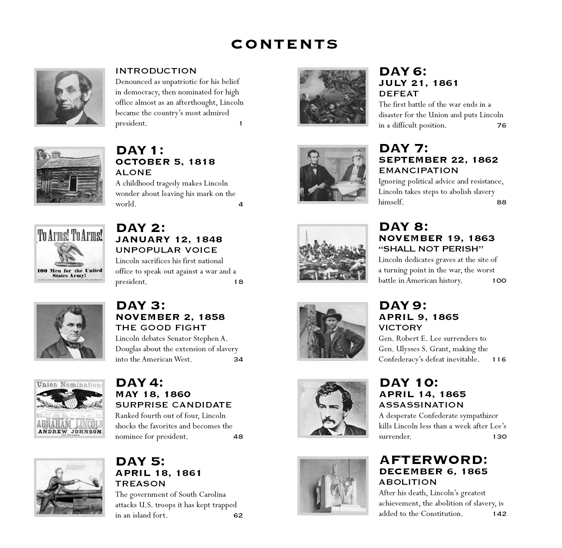

Abraham Lincoln lived 20,517 days. These 10 shook his world—and yours.

Introduction

The people who rise to the top aren’t always the heroes their biographies make them out to be. Abraham Lincoln, however, has become the gold standard by which other presidents are judged, and by which many of them judge themselves. Historians and the general public almost always place him in the top spot when presidents are ranked.

Yet during his lifetime, Lincoln was called unpatriotic and even a tyrant. When he was elected to the presidency, members of his own party questioned his ability. During the war, his judgment was questioned. Afterward, a large part of the population hated him.

To a large extent, we revere him now because we live in a world he helped to create. We’re taught and believe, as he believed, that Americans should enjoy equal rights and status under the law. We believe that the government of the United States derives its authority from the people, and exists to serve them.

These may seem like simple and obvious ideas, almost too childish to mention in our modern, complex world; but in Lincoln’s lifetime there were serious doubts that people could govern themselves. Lincoln was born in 1809, less than thirty years after the American Revolution ended, and just twenty years after the Constitution established our present form of government (the presidency, Congress, and the Supreme Court.) That early period in the country’s history was marked by many disputes among the states and between the states and the federal government. Throughout Lincoln’s life, the countries of Europe still expected the American experiment with democracy to end in chaos. The Civil War was seen by some as the final breakdown.

Although Lincoln’s simple ideals were ridiculed by his political opponents and by his rivals within his own party, he stuck to them at a time when other politicians became lost in complexity. That’s an important reason Lincoln’s vision of the country has prevailed. What’s far less simple is the route Lincoln took to reach his goals. “I claim not to have controlled events,” he said, “but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” Though he was being too modest, there’s some truth in that statement, even when it comes to his most admired achievement, the end of slavery.

If people know nothing else about the Civil War, they know it ended slavery. If they know only one thing about Lincoln, it’s that he freed the slaves. But those one-line versions of history focus on the final results of a process that took place over many years and could have moved in many different directions.

Lincoln, like the country, moved step by small step toward the end of slavery. Had the South not split from the United States and attacked it, Lincoln might not have used his presidential power to abolish the institution. Although he very much wanted slavery to end, he also believed the Constitution and other laws protected it where it already existed. Even during the Civil War there were slave states in the Union—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia. Lincoln offered to pay the slave owners of those states if they would free their slaves, and worked hard to get them to agree, but when they refused he didn’t impose his will on them. He believed, probably correctly, they’d try to join the Confederacy if he forced his wishes on them.

Even his famous Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free those Union slaves. It had effect only in the Confederate territory then under control of the U.S. Army. In what now may seem like an unusual twist of history but at the time was a tragedy, slavery existed in the Union states of the north until several months after the Civil War had freed the slaves of the South.

The complicated path to some simple ideas is what this book is about. It doesn’t contain many of the fun stories that have become standard for biographies of Lincoln: He was a great wrestler, he could really swing an axe, and he grew a beard because a young girl asked him to do it. It’s about the larger questions facing the country during his lifetime, and the answers Lincoln offered. In the ten days of his 20,517 described in the chapters that follow, the ten that most changed his life and yours, the changing fortunes of two rival armies may mean less than the change that took place in the minds of most Americans.

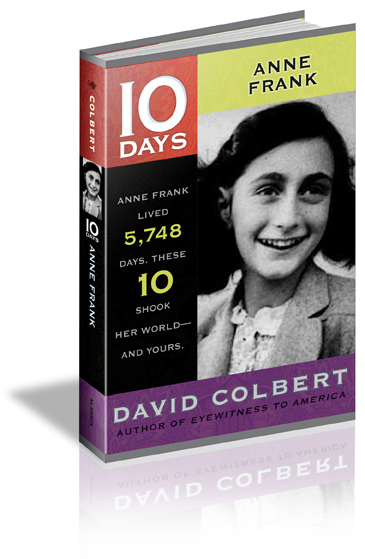

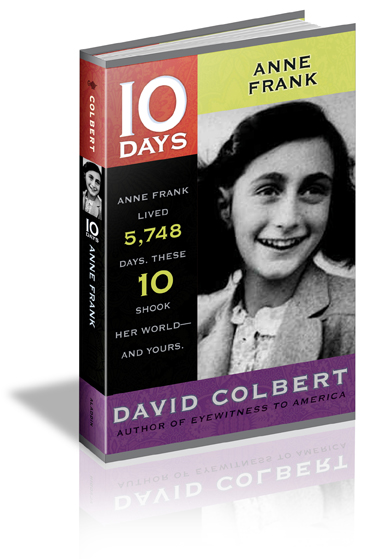

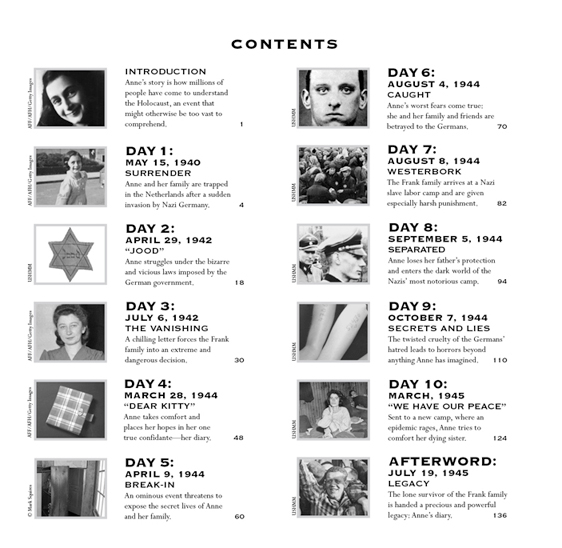

Anne Frank lived 5,748 days. These 10 shook her world—and yours.

Introduction

The short life of an ordinary schoolgirl may seem to be an unlikely subject for a biography. Yet when we read about Anne Frank, we defy what Nazi Germany hoped to achieve. The Holocaust was meant to be nameless—the Nazis tattooed numbers on most of their victims instead. Some of the world’s first large computers, sold to the Nazis by the American company IBM, literally reduced the victims to old-style computer punch cards. So the personal story of every Holocaust victim is an act of defiance simply because it’s personal.

It’s easy to quote statistics: six million Jews murdered—90 percent of the Jewish population of Poland, Germany, and other European countries. More than three million Poles, Slavs, Communists, Socialists, pacifist Christians (primarily Jehovah’s Witnesses), Gypsies (Roma), homosexuals, disabled, and people of African descent bring the total murdered to perhaps eleven million.

However, those statistics, shocking as they are, say nothing about the experience. You can only memorize numbers like those; you can’t feel them. The story of a single life can tell you more about the Holocaust than any statistic, no matter how large. Without stories like Anne’s, the Holocaust would be too vast to comprehend.

Anne’s life began just as the Nazis rose to power and ended just as the Nazis were defeated. She knew almost every part of the experience: what it felt like to have Nazi soldiers invade her neighborhood, to be branded as less than human, to live in hiding, to have a family separated into different death camps, and to be a prisoner of people who took a bizarre pleasure in cruelty. Like millions of others, she knew what it felt like to be murdered, slowly, by Nazi Germany.

Yet she also knew what it felt like to laugh during those horrible times. She watched movies with friends. She had crushes. She tried to get out of schoolwork. She had all the usual arguments with her mother that any girl her age might have. Anne understood that even any normal day under Nazi rule, even a dull day, was a victory for her and her family.

Anne lived approximately 5,748 days. (Because of conditions in her concentration camp, her exact date of death remains unknown.) Still, because of the events of the ten days that follow, she left her mark. These days changed her world—and yours.

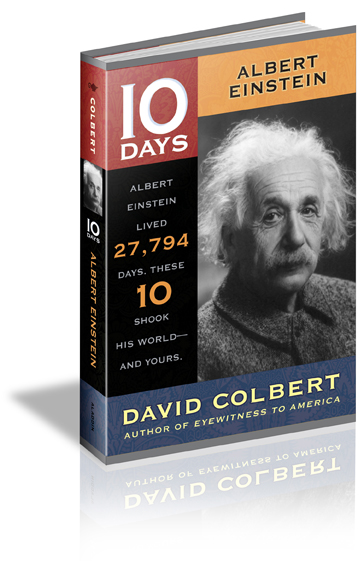

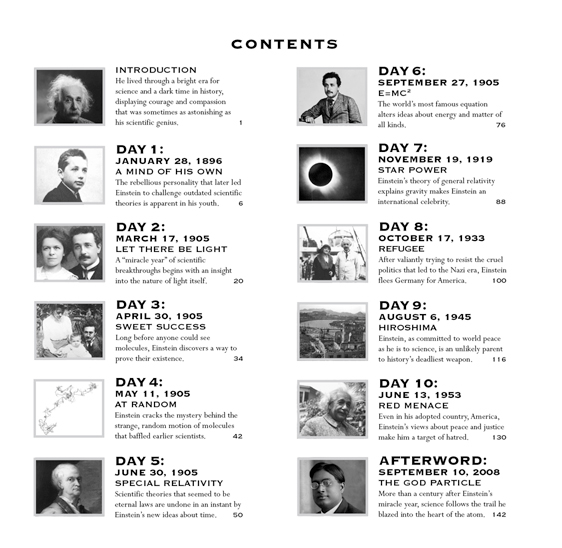

Albert Einstein lived 27,794 days. These 10 shook his world—and yours.

Introduction

Was Einstein the greatest mind ever? That’s the popular notion. Born before atoms were considered real, by the time he died the atomic age was well under way, thanks largely to him. Many scientists think Einstein’s genius was even greater than Isaac Newton’s, whose ideas dominated science until Einstein came along. Einstein surely would have scoffed at the idea of such measurements and comparisons. He didn’t seek and wasn’t interested in that kind of recognition. He never hid the fact that his accomplishments came after many mistakes, and that the last half of his life was spent in a frustrating search for a single theory that would tie together his earlier work.

Ignoring his modesty, the press loved to push him into the spotlight whenever it could. His appearance fit the stereotype of a genius whose mind was in the clouds: the wild hair, the casual sweatshirts, the fact that he rarely wore socks, even on formal occasions. His quirks were endearing.

He always made for a good story. When he wasn’t turning the accepted laws of nature upside-down, he was challenging governments all over the globe to act responsibly. He was often criticized for being out of touch with the real world, but the opposite was true. He wasn’t lost in a world of atoms and equations. He was deeply concerned with the world of people. When a microphone or camera was stuck in his face, he was more likely to talk about social justice than his theories of space and time.

Religion, science, politics: three threads that ran through his life. He was clear about the role each played for him. The outside world, however, was often confused.

After an early bout of religious feeling as a boy, Einstein never regained any enthusiasm for organized religion. Still, he considered himself religious to the end of his life. His explorations of the cosmos had convinced him that behind everything “there remains something subtle, intangible and inexplicable,” he said. He was annoyed when atheists tried to claim him as one of their own. But because his scientific theories were contrary to the explanations found in some religions, he was attacked as immoral. This didn’t happen only in Nazi Germany, where being born Jewish led to him being attacked for having scientific ideas that were labeled “Jewish physics” and a threat to social order. Similar attacks occurred in America, too.

His political battles, whether with entire governments or with critics who were afraid of his ideas, often amused him as much as they irritated him. He liked being a rebel. He believed it was usually the right side of an argument. More often than not, history has proven him correct. A colleague once said, “There was in him a powerful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn.” He had been born into a culture, Germany of the late 1800s, that was ruled by an aristocracy and governed by unwritten rules that locked people into the social and economic classes of their birth. He demanded, and lived to see, the spread of democracy. But it wasn’t always easy. He was still living in Germany when the Nazis rose to power, and because of his religion, his science, and his politics, a price was put on his head. He didn’t have to be a genius to know he had to leave.

His approach to science was unusual. Most scientists perform experiments, observe what happens, and draw conclusions. Einstein accomplished the first part of that process in his head, with what he called “thought experiments.” He constructed visual pictures in his mind of how an answer ought to look—which meant looking for the simplest possible answer. Then he looked at how it would work, drawing on his mathematical skill. It may not work for every kind of science, but it worked for him. He was studying the world at an atomic level before atoms had even been proved to exist, so no measuring device of the time could have shown him what he could see with his imagination. In some cases it took the invention of huge devices (a few of them several miles wide) to confirm Einstein’s theories, but his work was done with pencil and paper and the stuff between his ears. He once wrote, “I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know His thoughts; the rest are details.”

The independence of his mind was as important as its processing power. Without his willingness to ignore apparently obvious “truths” about space, time, and light, our modern world would be very different. His work led to the development of televisions, lasers, computer processor chips, even today’s Global Positioning System (GPS) devices. Yet while he was a rebel when it came to methods and ideas, his kindness was legendary. High school students discovered he would help them with their homework. Everyone remarked on his essential sweetness and his humor. It was those qualities, along with his intelligence, that made him so beloved. Even in his later years, when he was frustrated that he couldn’t catch the elusive theory he’d been chasing for a few decades, he remained essentially happy. Imagining and examining the scientific possibilities of the universe held an irresistible magic for him.

“One cannot help but be in awe when one contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality,” he wrote. “It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery each day.” That’s exactly what he did for most of his 27,794 days. Here are the ten that changed his world—and yours.

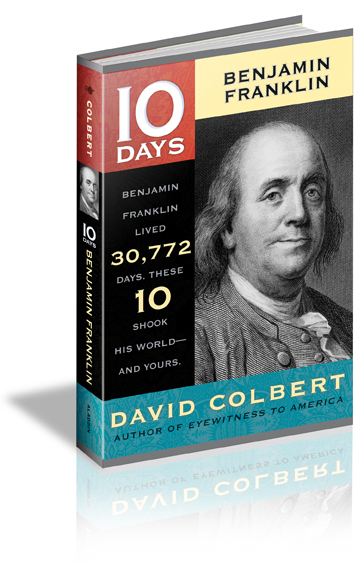

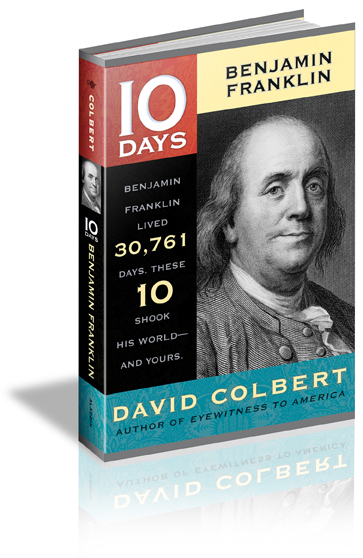

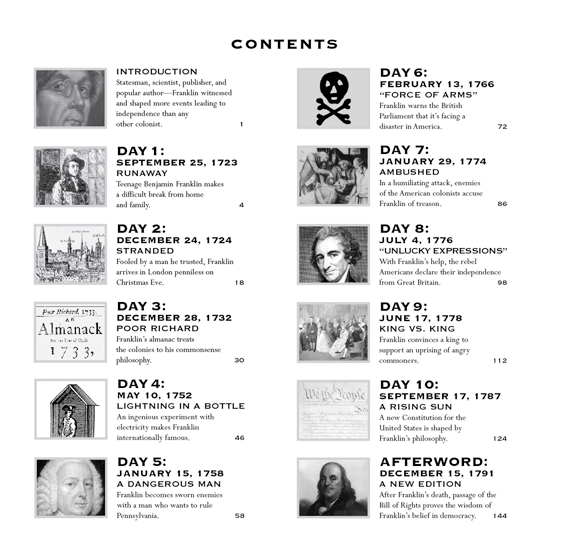

Benjamin Franklin lived 30,772 days. These 10 shook his world—and yours.

Introduction

Statesman, scientist, publisher, and popular author—Benjamin Franklin witnessed and shaped more events leading to independence than any other colonist. He represented the colonies in Britain. He signed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. He negotiated the treaty with France that helped win the Revolution, and the peace treaty with Great Britain that ended the war.

With just two years of traditional schooling, he became a celebrated philosopher and scientist. He discovered rules about electricity that are still taught today. Some of his many other scientific observations were more than a century ahead of their time.

Long before governments began to provide services to their citizens, he helped organize firefighters, schools, and a hospital.

His books were bestsellers. Some were translated and published across Europe. Lines he wrote are now common phrases.

He had remarkably few enemies for a man who played a part in creating a new, complex nation. When he made an enemy, there was usually a reason. By nature he was an optimist. He gave his trust generously and found that even difficult people gave him their trust in return.

He also had faults. He was obsessed with financial success and in business occasionally left people feeling misled. Though he preached often about avoiding vanity, at times his modesty was an act. His optimism sometimes blinded him to reality: He failed to understand for a long time that Britain’s king, George III, would never give the colonists the rights they demanded. He was against slavery as an institution, but he owned slaves for a while and printed advertisements for slaves. For part of his life he held the usual prejudices against African Americans, slave or free. However, it must be said that he came around to the idea that “the black race” was “in every respect equal” to his own, which was a rare belief at the time, even among those people who wanted to end slavery.

He’s an icon now, but he was a man once. He had his good days and his bad days, his boring days and his interesting days. He lived 30,772 days in all. Here are the ten that shook his world—and yours.

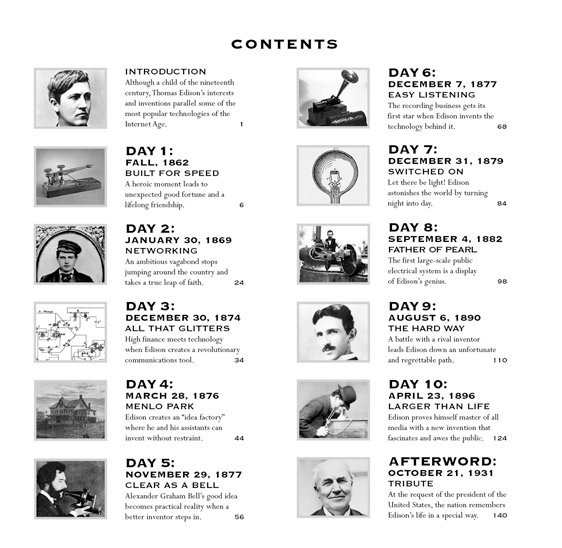

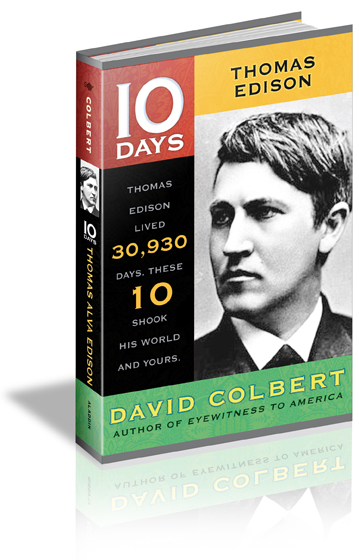

Thomas Edison lived 30,930 days. These 10 shook his world—and yours.

Introduction

In an age when ships and trains ran on steam, Thomas Edison was building an early version of the Internet. He was wiring the world when that meant actually climbing on rooftops to run the wires. This was even before electrical power plants existed. You couldn’t plug an appliance into a wall outlet, because there were no outlets. Everything ran on crude, acid-filled batteries. Yet Edison’s inventions will seem familiar to anyone who uses the Internet today. He pioneered text messaging, making it possible for multiple messages to be sent at once, just as today’s computers do. Later he added voice technology. Then, while trying to invent voice mail, he came up with portable music. A few years afterward he created a popular video-clip player that works on the same principle as YouTube—in fact, some of the video clips he created can be seen on YouTube today.

Somewhere in the middle of all this he invented the lightbulb.

If Edison were alive now he’d be running a company in Silicon Valley. The research and engineering systems he developed became admired models for business. He knew how to deal with venture capitalists and the stock market. He was brilliant at publicity. He also knew what Microsoft, Apple, and every other successful Silicon Valley company of today knows: how to improve a competitor’s idea and turn a laboratory theory into a must-have gadget.

Most of the best-known photographs of Edison show him as an old man with gray hair, creating a false impression of a grandfatherly tinkerer. Actually, he was young during his most creative period. He was in his early twenties at the time of his first success, and just over thirty when the lightbulb was invented. He attacked every project with intense drive. In all-night sessions at his laboratory, he would think of dozens or even hundreds of possible solutions to the problem at hand, then he and his assistants would try each one. He was a lot like young people today who have always lived in a wired world and understand the new technology better than many adults. The same generation gap existed in his time. He was the Boy Wonder.

Over the course of his life, technology exploded. When he was born in 1847, railroads and the telegraph were new. If you wanted to travel fast or get a message to someone quickly, your best choices were horseback or riverboat. If you were an inventor, you had to make most of your parts by hand. If you were making an electrical gadget, you had to create your own electrical power. When Edison wanted to bring electric light to New York City, he had to build the country’s first power station. But by the time Edison died in 1931, there was photography, motion pictures, the telephone, the airplane, the automobile, the X-ray, air-conditioning, television, all sorts of appliances—and the world was lit with electric light.

“Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration,” he said. He certainly was not an accidental success. He had enormous ambition. Sometimes, however, that ambition propelled him far along a course he should have abandoned. Because he was essentially self-educated and self-made, and had achieved great success, he tended to trust his instincts even when evidence suggested he was wrong. This led to trouble a few times. He missed some great opportunities for his discoveries. He refused to acknowledge better technology created by certain competitors. He sometimes cut ethical corners.

Still, most of the 30,930 days he lived were filled with fascinating attempts at discovery and invention that foreshadow the most modern inventions of the electronic age. Here are the ten days that changed his world—and yours.